A work——what I call the use of my time

What a huge number of concepts and feelings it has corrupted and poisoned! At the so-called evening grammar school organized by the Dresden adult education centre, and in the discussions organized by the Kulturbund {Cultural Association} and the Freie deutsche Jugend {Free German Youth}, I have observed again and again how the young people in all innocence, and despite a sincere effort to fill the gaps and eliminate the errors in their neglected education, cling to Nazi thought processes. They don’t realize they are doing it; the remnants of linguistic usage from the preceding epoch confuse and seduce them. We spoke about the meaning of culture, of humanitarianism, of democracy and I had the impression that they were beginning to see the light, and that certain things were being straightened out in their minds – and then, it was always just round the corner, someone spoke of some heroic behaviour or other, or of some heroic resistance, or simple of heroism per se. As soon as this concept was even touched upon, everything became blurred, and we were adrift once again in the fog of Nazism. And it wasn’t only the young men who had just returned from the field or from captivity, and felt they were not receiving sufficient attention, let alone acclaim, n, even young women who had not seen any military service were thoroughly infatuated with the most dubious notion of heroism. The only thing that was beyond dispute, was that it was impossible to have a proper grasp of the true nature of humanitarianism, culture and democracy if one endorsed this kind of conception, or to be more precise misconception, of heroism.

those with head wounds inflicted by beer mugs or chair legs were Nazis, and those with a stiletto wound in the lung were Communists.

Chronologically the second uniform in which Nazi heroism clothed itself is the masked figure of the racing driver, his crash helmet, his goggles, his thick gloves. Nazism nurtured all kinds of sport, and purely linguistically it was influenced by boxing more than all the others put together; but the most memorable and widespread image of heroism in the mid-‘thirties is provided by the racing driver: following his fatal crash, the image of Nerd Rosemeyer was almost as cherished in the nation’s popular imagination as Horst Wessel. (Note for my university colleagues: the most fascinating seminars can be spent investigating the reciprocal relationship between Goebbels’s style and the memoirs of the aviator Elly Beinhorn: “My Husband, the Racing Drive {Mein Mann, der Rennfahrer}’.) For some time the champions of international motor races were the most photographed heroes of the day, seated behind the steering wheels of their chariots, leaning against them or even buried beneath them. If a young man didn’t glean his image of heroism from those sinewy warriors depicted on the latest posters or commemorative coins, naked or sporting SA uniforms, the he doubtless did so from racing drivers; what the two incarnations of heroism have in common is the glassy stare which expresses a hard and thrusting determination coupled with the will to succeed.

For twelve years the concept and vocabulary of heroism are increasingly and ever more exclusively restricted to military bravery and foolhardy, death-defying behaviour in some military action or other. It is not for nothing that the language of Nazism introduced into common usage the word ‘kämpferisch {aggressive, belligerent}’, a new and rarely used adjective associated with Neo-Romantic aesthetes, fashioning it into one of its favourite words. Kreigerisch {warlike} was too narrow, it only intimated things relating to war itself, it was also probably too candid, betraying an aggressive disposition and mania for conquering. Kämpferisch is quite a different matter! It denotes in a more general way that taut frame of mind and will which in any situation is focused on self-assertion through defense or attack, and which refuses to countenance any form of compromise. The abuse of kämpferisch corresponds perfectly to the excessive damage done to the word heroism when it is used inappropriately or wrongly.

observe, study and memorize what is going on – by tomorrow everything will already look different, by tomorrow everything will already feel different; keep hold of how things reveal themselves at this very moment and what the effects are.

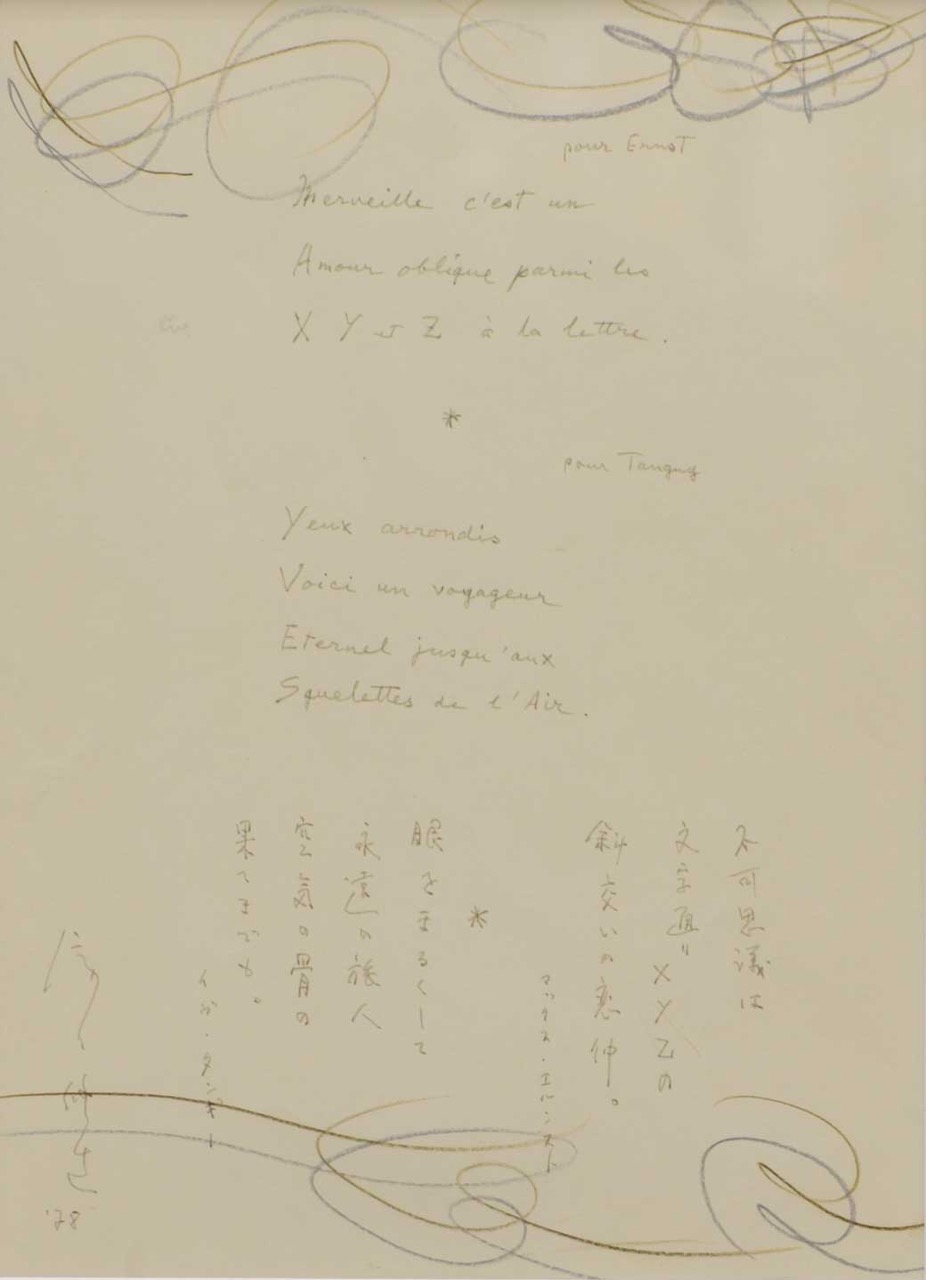

People are forever quoting Talleyrand’s remark that language is only there in order to hide the thoughts of the diplomat (or for that matter of any other shrewd and dubious person). But in fact the very opposite is true. Whatever it is that people are determined to hide, be it only from others, or from themselves, even things they carry around unconsciously – language reveals all. That is no doubt the meaning of the aphorism Le style c’est l’homme; what a man says may be a pack of lies – but his true self is laid bare for all to see in the style of his utterances.

Right at the outset, while I was still suffering no persecution, or at most a very mild form, I wanted to hear as little as possible of it. I had more than enough of it in the language of the window displays, the posters, the brown uniforms, the flags, the arms outstretched in the Hitler salute, the carefully trimmed Hitler moustaches. I took flight, I buried myself in my profession, I gave my lectures and desperately ignored the increasingly yawning gaps in the rows of seats in front of me, I exerted all my energies on my eighteenth-century French literature. Why should I sour my life still further by reading Nazi publications when it was already being ruined by what was happening around me? If by chance or mistake a Nazi book fell into my hands I would cast it aside after the first paragraph. If the voice of the Führer or his Propaganda Minister was blaring out of a loudspeaker on the street I would give it a wide berth, and when reading the newspaper I desperately tried to fish out the naked facts – forlorn enough in their nakedness – from the repulsive morass of speeches, commentaries and articles. When the civil service was purged and I no longer had my lectern to lean on, my initial reaction was to try to cut myself off from the present entirely. Those thoroughly unmodern Enlightenment thinkers, long since despised by anybody who thought they were anybody, had always been my favourites – Voltaire, Montesquieu and Diderot. I could now dedicate all my time and energy to my opus which was already well advanced; as far as the eighteenth century was concerned I was in clover in the Japanese Palace in Dresden; no German library, and perhaps not even the national library in Paris, could have served me better.

But then came the next blow in the form of the ban on library use, pulling my life’s work away from under me. After that I was driven out of my own house and everything else followed, every day something new.

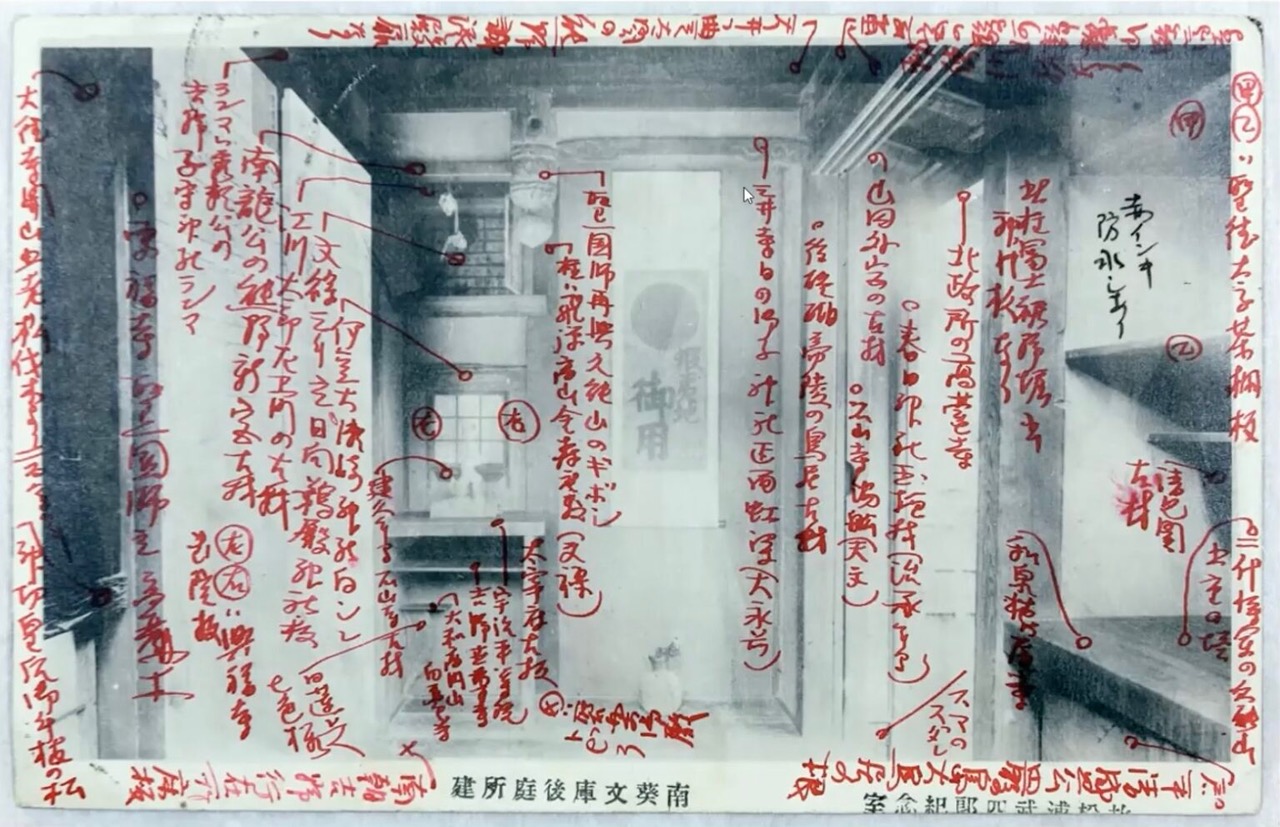

There are therefore again and again remarks such as the following in my notes and excerpts: Check later! . . . Amplify later! . . . To be answered later! . . . And then as the hope of experiencing any kind of ‘later’ begins to ebb: This would have to be tackled at a later date . . .

Today, when this ‘later’ has not yet quite arrived, but will do so when books emerge once again from the rubble and the traffic chaos (and when one can withdraw to the study with a good conscience from the communal vita activa of rebuilding) – today I know that I will not in fact be able to transform my sketch-like observations, reflections and questions on the language of the Third Reich into a well-knit academic work.

That would demand more knowledge, and indeed a longer life, than I or (for the time being) any other individual has at his disposal. For there is a lot of specialist work to be done in many different areas, Germanists and scholars of the Romance languages, English specialists, and Slavonicists, historians and economists, lawyers and theologians, engineers and scientists will have to solve innumerable individual problems in excursuses and entire dissertations before it will be possible for a courageous and comprehensive mind to attempt to characterize the Lingua Tertii Imperii in its entirety, in its most pitiful and most wide-ranging entirety. But an initial groping around and probing of these things – things which cannot yet be pinned down because they are still in flux – the work of the first hour, as the French describe this kind of thing, will certainly always be of value to the real researchers who will follow, and I think it will also be useful for them to see their object of study still in the process of metamorphosis, half as a concrete report on lived experience and half within the conceptual framework of an academic study.

Nazism permeated the flesh and blood of the people through single words, idioms and sentence structures which were imposed on them in a million repetitions and taken on board mechanically and unconsciously. One tends to understand Schiller’s distich on a ‘cultivated language which writes and thinks for you’ in purely aesthetic and, as it were, harmless terms. A successful verse in a ‘cultivated language’ says nothing about the literary strengths of its author; it is not particularly difficult to give oneself the air of a writer and thinker by using a highly cultivated turn of phrase.

But language does not simply write and think for me, it also increasingly dictates my feelings and governs my entire spiritual being the more unquestioningly and unconsciously I abandon myself to it. And what happens if the cultivated language is made up of poisonous elements or has bene made the bearer of poisons? Words can be like tiny doses of arsenic: they are swallowed unnoticed, appear to have no effect, and then after a little time the toxic reaction sets in after all. If someone replaces the words ‘heroic’ and ‘virtuous’ with ‘fanatical’ for long enough, he will come to believe that a fanatic really is a virtuous hero, and that no one can be a hero without fanaticism. The third Reich did not invent the words ‘fanatical’ and ‘fanaticism’, it just changed their value and used them more in one day than other epochs had used them in years. The Third Reich coined only a very small number of the words in its language, perhaps – indeed probably – none at all. In many cases Nazi language points to foreign influences and appropriates much of the rest from the German language before Hitler. But it changes the value of words and the frequency of their occurrence, it makes common property out of what was previously the preserve of an individual or a tiny group, it commandeers for the party that which was previously common property and in the process steeps words and groups of words and sentence structures with its poison. Making language the servant of its dreadful system it procures it as its most powerful, most public and most surreptitious means of advertising.

The task of making people aware of this poisonous nature of the LTI and warning them of its dangers is, I believe, not just schoolmasterish. If a piece of cutlery belonging to orthodox Jews has become ritually unclean they purify it by burying it in the earth. Many words in common usage during the Nazi period should be committed to a mass grave for a very long time, some for ever.